When We Don't Say What We Mean

Why We Lose Our Voice in Everyday Conversations (And How to Get It Back)

Editor’s note:

This week, I’m handing the page to Dr. Jane Bormeister, speech scientist, rhetoric coach, and my collaborator on the Eating & Speaking challenge launching Monday.

I study what happens before you speak: the body state that determines whether you’ll have access to your voice at all.

Jane studies what happens when you speak: why the words disappear in the moment, and how to get them back.

Her piece today is about the moments we lose our voice — not in boardrooms, but in kitchens, on client calls, and in the conversations that actually shape our lives.

Ready to join us? The challenge starts Monday February 23. We’ll go live at 2:15pm Eastern Time, and 8:15pm Berlin Time.

For now, I’ll let Jane take it from here.

—Savitree

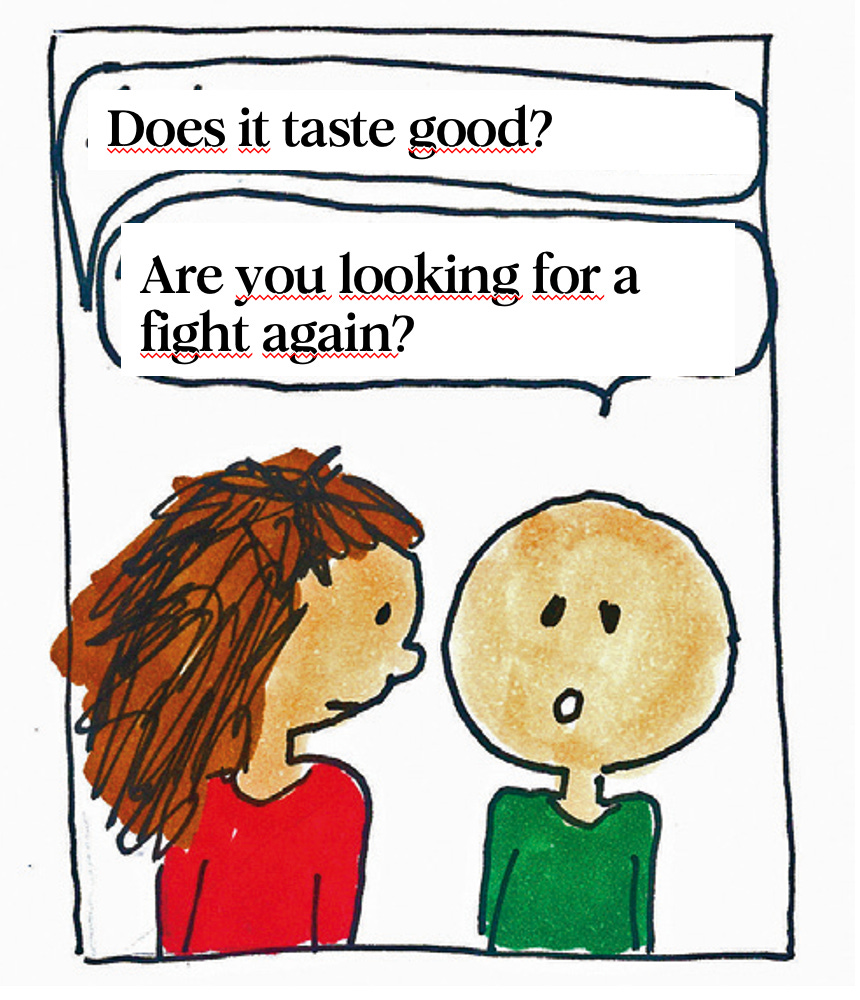

The conversations where we lose our voice don’t just happen in boardrooms. They happen in our home office during client calls. In discussions with our partner about responsibilities. In negotiations where we give in, even though we know something doesn’t feel right.

Someone asks, almost casually: ‘Could we revisit the budget?’ ‘Could you also take this on?’ ‘Would it be possible for you to...’

In that moment, everything is clear. The answer is: No. Not now. Not today. Not again.

And yet we say: “Yes... sure.”

This happens everywhere. On Zoom calls. On the phone. Even in our own kitchen.

Afterwards, something lingers. A tightness in the chest. A quiet anger, often at ourselves.

The question isn’t: Why didn’t I find the right words?

But rather: Why didn’t I have access to myself?

What happens in these situations?

Many believe such moments stem from poor boundaries. Or lack of courage. Or wrong words.

But when you look closely, something else is happening.

The body tenses up. Breathing becomes shallow. The voice gets quieter, faster, shakier.

Some talk too much. Others not at all.

Only later, while doing dishes or sitting in the car, do we suddenly know exactly what we should have said.

The problem isn’t missing clarity. It’s a loss of access.

The invisible role trap

We never speak just as “ourselves.”

We switch roles. Constantly.

Partner. Mother. Organizer. Helper. Entrepreneur. In the kitchen, the partner suddenly becomes the project manager of family life.

The role takes over before we notice it.

And each role brings its own voice.

As organizer, the voice sounds faster, more efficient. As helper, softer, more explanatory. As mother, shorter, often sharper. As partner, more cautious, sometimes irritated. And as daughter, we can suddenly be ten years old again—even at forty-five.

None of these voices is wrong. But not every one fits the role we’re currently playing.

The problem isn’t that we have roles. It’s that they often speak unnoticed.

Sometimes we realize it mid-sentence: That’s not how I wanted to say that.

In these moments, body, voice, and word are no longer in sync. What gets said is often not wrong. Just not aligned.

Speaking authentically doesn’t mean saying everything you think. It means noticing which role you’re speaking from and whether that role is appropriate.

Captain Rhetoric would say: “You didn’t betray yourself. You just weren’t present with yourself for a moment.”

What voice research shows

Voice research confirms exactly this.

Studies with people in speech-intensive professions show: Knowledge alone isn’t enough (Nallamuthu et al., 2021).

Even when people know exactly:

how they should speak

what’s good for their voice

what they should avoid

they fall back on old patterns under pressure.

Not from carelessness. But because the body has no access to what was learned in those moments.

A study with teachers found: After a structured voice hygiene program, the women knew exactly what to do. They drank more water, cleared their throat less, ate healthier.

But under real stress—30 children in the classroom, noise, chalk dust—they still reverted to old patterns. The researchers conclude: “Efficiency was limited when it came to achieving actual improvements” (Nallamuthu et al., 2021).

Under stress, it’s not the head that decides. But the state we’re in.

The latest voice research shows: Everyone needs their own approach. Not a universal list of “do this, don’t do that,” but the very personal factors that throw us off balance (Weston & Schneider, 2023).

The Rhetoric Code

In my work, I call this the Rhetoric Code: the connection between body, voice, and word—in relationship to each other and to others.

When this connection holds, we speak clearly—in the home office, in negotiations, in conflict.

When it breaks, we lose our voice long before we say anything.

Why eating is the starting point

So the question is: How do we ensure this connection holds, even under pressure?

This is where eating comes in. Eating is important. But here it’s about something else: eating as a daily, physical anchor.

When the body is permanently under time pressure, it can’t access presence, no matter how good the technique is.

Our joint challenge Eating & Speaking starts exactly here: not with new rules, but with a 21-day experiment.

You don’t change your whole life. You change one moment in the day and observe what this does to your voice, your clarity, and your presence.

Not on stage. But where your life happens. Between appointments. Between people. In the kitchen.

References:

Nallamuthu, A., Boominathan, P., Arunachalam, R., & Mariswamy, P. (2021). Outcomes of vocal hygiene program in facilitating vocal health in female school teachers with voice problems. Journal of Voice, 35(4), 647.e1-647.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.12.041

Weston, Z., & Schneider, S. L. (2023). Demystifying vocal hygiene: Considerations for professional voice users. Current Otorhinolaryngology Reports, 11(4), 387-394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40136-023-00494-x